Approximately 90% of international trade is conveyed by containerised sea freight, and we have indeed seen a paradigm shift in container freight rates from pre-pandemic to current.

The Covid-19 pandemic is an unprecedented event that has brought, and continues to bring with it, an array of challenges, inter alia, a supply chain quagmire with several ensuing conundrums. After critical analysis and careful evaluation of fundamental economics concepts, together with an overview of the pandemic and the market structure of the shipping industry, we are able to carefully project the trend of freight rates as we conclude the last quarter of 2021 and head into 2022.

One would recall, when the pandemic was in its infancy, there was indeed a high level of uncertainty surrounding the mechanics and possible progression of the virus. Very little was known and very little research was available to guide informed decisions, resulting in several initial “hard lockdowns” that virtually brought supply chains to a standstill. Containers were stranded at ports, incurring demurrage charges, equipment shortage would soon ensue, port schedules were disrupted as vessels were detained and others prohibited from calling at certain geographical locations, resulting in altered trade lane routes. Factories that manufactured goods for export were also adversely affected insofar as production lines were concerned, resulting in a shortage of supply to export markets.

Having said that, containers are often regarded as the building blocks of the supply chain and, as indicated in the opening statement, form an integral component of international trade. Having said that, one would soon be able to deduce that it was only a matter of time that supply would become scarce and, based on the fundamental principles of the law of supply and demand, demand would begin to rise, and so too would the prices.

We further take cognisance of the fact that oil prices plummeted at the initial stages of the pandemic, and similarly once lockdowns eased and supply chains mobilised again, the demand for oil increased, resulting in an increase in the selling price. The shipping industry indeed can invariably be categorised as an oligopoly market structure whereby a few major players dominate the market.

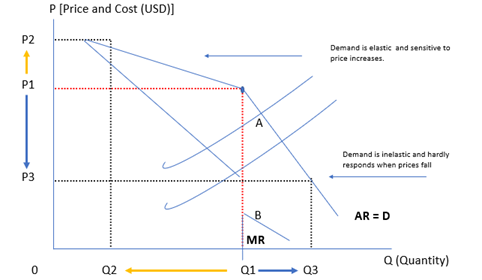

If a shipping line raises its price from P1 to P2, quantity demanded will decrease, however this decrease is proportionately more than the increase in price. Competitors will therefore maintain their price at P1, looking to gain market share and thus undercut the shipping line who raised their price. A small increase in price results in a large decrease in demand and oligopolists therefore do not look at price adjustments but rather other avenues and mechanisms to gain market share.

If a shipping line decides to significantly decrease their price from P1 to P3, the law of demand provides that there will be an increase in demand; however the demand is proportionately less (as we can see from Q1 to Q3) in relation to the massive decrease in price from P1 to P3. This is now the price inelastic portion of the demand curve (not in the shipping lines’ best interests). The reason for the disproportionate relationship between price decrease and demand increase is due to how other shipping lines would react. Other shipping lines will follow, looking to protect their market share, total revenue will decrease, over time market share will remain unchanged (no gain), hence price rigidity or stickiness in oligopoly market structure and shipping lines don’t need to change their price.

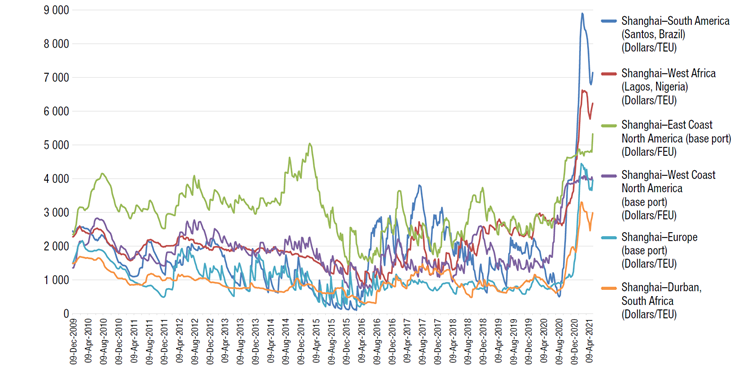

As we can see from the orange line in the above diagram, average freight rates for containerised cargo from Shanghai to Durban moved from above the US$1000 mark in April 2020 to just around the US$3000 mark in April 2021, a year-on-year increase of 200% - and this increase was soon dwarfed by a 1000% increase, with rates averaging around US$9000 per 40-foot container in September 2021. The reasons for the significant increase are discussed in the preceding paragraph - and of course an informed insight into the continued trajectory is provided in the ensuing summary.

As elaborated early on, container freight rates will indeed begin to fall, even though they will still be considerably higher than pre-pandemic levels as the demand continues to exceed supply, stabilising once the plateau has been reached. In the economic literature, the shipping sector and container handling are referred to as a global market that takes the form of an oligopoly in which a few main global players handle a substantial share of capacity in the main trades (Sys, 2009).

First, while barriers to entry within container shipping will likely remain relatively high (at least for new players looking to achieve enough scale to acquire meaningful influence over marginal industry pricing), there will always be incentives facing individual liners to attract marginal cargoes, and where pricing is concerned the industry does, in theory, remain competitive.

The second reason why freight rates may well eventually trend back close to pre-pandemic levels is that, leaving to one side questions around the theoretical price of low-carbon fuels later in the decade, liner company cost bases have not radically shifted relative to pre-pandemic trends, and in a competitive and commoditised industry marginal costs will in theory retain an important influence on industry pricing.

Finally, and really this is the key to how freight rates will develop once pandemic-specific factors are removed, looking beyond 2022 there is a lot of capacity hitting the water. From the industry’s present vantage point, it can feel difficult to imagine how the current market conditions could ever end, and there seems to be a general sense of confidence that the volume of deliveries will be relatively easy to absorb.

But, at a fundamental level, if you deliver over 2.0 million TEUs, or approaching 10% of the fleet, per year, for several years running, this will have consequences. This will not be an issue before 2023, and, most likely later in that year, unless the demand environment worsens beyond current expectations. Increased slow steaming could also offset capacity increases to some degree. But with container trade growth unlikely to exceed 4% per annum in a ‘normal’ year, several years of fleet growth closer to – or in excess of – 6% per annum will provide the real test of whether the industry has truly left the pre-pandemic world behind for good.

In the words of Lawrence J Peter, “Economics is the art to meet unlimited needs with scarce resources”.