Cross-border truck drivers using the Maputo Corridor were stuck inside their cabins for a week or more because of intermittent border post closures caused by political unrest in Mozambique over the festive season.

Trapped in an ever-extending queue at South Africa’s Lebombo Border Post on the N4, by day the drivers relieved themselves in the bush, often taking baths using water from mud puddles on the side of the road.

Informal trade from Komatipoort spiked, helping drivers get by through cold drinks and soft produce sold from plastic buckets and skottels on the heads of women walking up and down the queue.

At night, when the sweltering summer heat had given way to oppressive humidity, it was a different story, as drivers often became prey to criminals who worked the line.

Having a decent night’s rest in such conditions is almost impossible as drivers dare not sleep too deeply lest the back-up start edging forward.

Sometimes, marshalls, ‘standing in’ for law enforcers, will bang loudly on cabin doors of trucks not moving when they should.

Shambokking isn’t ruled out.

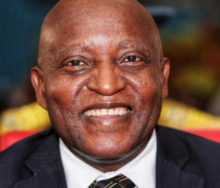

One tip-truck driver who is now carrying chrome and coal on the N17, entering Eswatini at South Africa’s Oshoek Border Post and passing in Mozambique at the Lomahasha-Namaacha transit, is 40-year-old Donald Galeng.

Following a life-threatening experience heading towards the Matola Bulk Terminal at the Port of Maputo, he said in December he had to wait 10 days before finally finding himself back in South Africa.

On the outskirts of Maputo he encountered protestors at a makeshift road barricade demanding ‘toll’ if he wanted to proceed to port.

“I was very scared. I didn’t leave my truck because I didn’t know what they would do. My boss had to send me money so I could pay them.”

Galeng said once he had offloaded at the terminal, he was advised against leaving because of escalating security threats on the road to the Ressano Garcia Border Post.

“They said I mustn’t go so I waited a few days.”

At this stage, he had made peace with what he had lost at the barricade – clothes and some personal effects and, of course, the ‘toll’ he was forced to pay.

What he wasn’t going to do was risk his life.

“I saw what was happening. Some drivers have died in Mozambique.”

Finally, back on the road after a week inside the port, Galeng sought safety for himself and his truck on the outskirts of Ressano, waiting three days before re-entering South Africa.

Now avoiding the N4 altogether, he said the N17 route through Eswatini was longer and the road through the border towards Boane, south-east of Maputo, was falling apart.

“You have to drive through villages, and it’s a long way around (compared with the Corridor), but at least you keep moving. You don’t have to stand and wait at the Komatipoort border.

He said he would probably have to use the Corridor again but only when it was safe.

Galeng added that drivers were eagerly awaiting the January 15 inauguration of Daniel Chapo, the Frelimo party’s elected presidential candidate, whom supporters of the opposition Podemos party claimed ‘stole’ the October 9 election.

“We’ll wait and see what happens then. Some drivers have said to the companies they work for they don’t want to drive in Mozambique because of the danger. But the bosses say, ‘If you don’t want to do the work we’ll get someone else’.

“I’m lucky. I’ve got chrome I loaded in Rustenburg and am heading to Durban.”