Five decades ago this October a conflict in the Middle East became the catalyst for a seismic shift in automotive design, production and performance, challenging all elements of logistics previously dependent on fossil fuels.

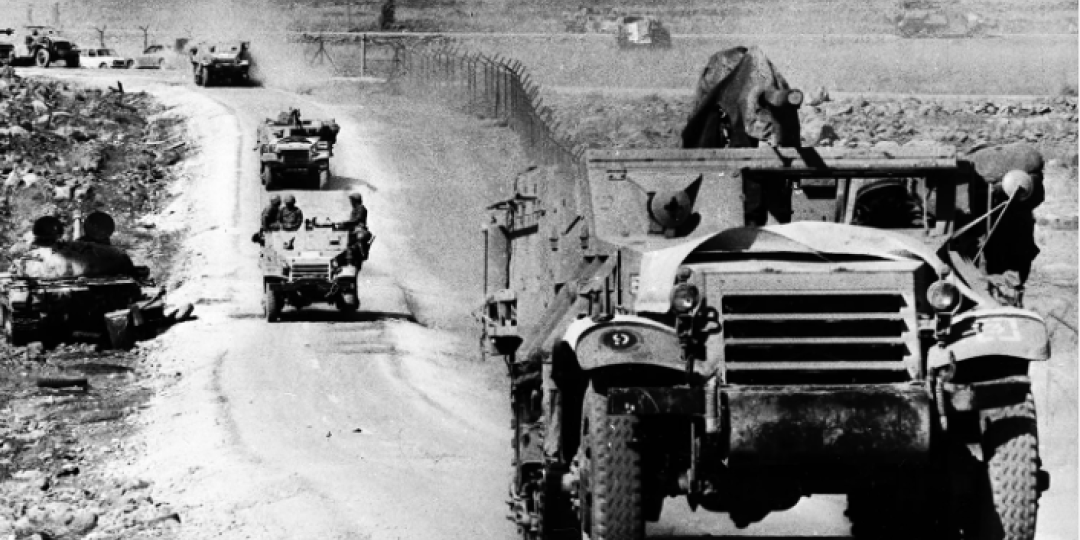

On October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack against Israel on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur.

The Egyptian and Syrian forces made early gains against the trimmed forces of Israel for the important holiday.

However, the Jewish state rallied with significant support from major Western powers and went on to secure Israel’s territory.

In retaliation for aid given to Israel by the West in the short conflict the members of the Organisation of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo targeted at nations that had supported Israel in what is today known as the Yom Kippur War.

Regarding the embargo, US oil imports from participating OAPEC nations were curtailed as they cut production which immediately increased the world price of oil.

These cuts nearly quadrupled the oil price from $2.90 a barrel before the embargo to $11.65 a barrel in January 1974.

South Africa, already battling international sanctions with regard to oil procurement because of sanctions for its apartheid policy, was badly affected, both in supply terms and the cost of “black market” clandestine purchases.

There were obviously price increases for South African motorists to contend with. The government also imposed restrictions on purchases and storage of fuel, rigid opening and closing times for filling stations, and sometimes ridiculous maximum speeds to reduce our need for the scarce resource.

Obviously, all elements of the logistics chain were affected – shipping, rail, road or air.

And, ever wonder how those strange highway dead stops exposing unfinished road overhangs got there in Port Elizabeth and Cape Town?

Well, it was mainly because of the 1973 Oil Crisis, according to the head of engineering for the South African National Roads Agency Limited (Sanral), Louw Kannemeyer.

This is how he explained it: “Road construction was financed by a levy imposed on the fuel price which was suddenly impacted upon by the government’s response to the crisis.”

The government of the day, he explained, tried whatever they could to reduce the number of litres of fuel consumed.

“So, the finance source necessary for road construction and maintenance was radically reduced and the brake was put on some construction, which never restarted.

“Hence, today you have these talking points that people have been pondering over if you drive in Cape Town and Port Elizabeth where there are unfinished highways to nowhere.”

Another little-known consequence of the oil embargo and the reduction in fuel consumption globally, is the cornerstone to overcoming global warming.

After 1973, emissions growth fell by 30% in Asia and 60% in Latin America and Africa. Global growth in carbon emissions fell from just under 5% annually in the decade before 1973 to less than 2% annually in the decades following it.

Officially, the embargo ended in March 1974, but the vulnerability of many countries to a reliance on Middle East oil speeded up the search for more oil sources and radical changes to vehicle design and drive trains.

Out went the “gas-guzzlers” boasting six, eight and even 12 cylinders as major selling attractions, and in came more efficient and aerodynamically superior vehicles of all sizes and for all applications.

This continues today with a different threat driving its need to save the planet.