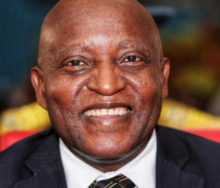

A multi-lateral infrastructural “game-changer” for sub-Saharan Africa that could add millions to South Africa’s electricity-related debt bill is again making headlines after energy minister Jeff Radebe pledged local buy-in for the construction of the Grand Inga Dam on the Congo River.

The project between SA, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and various interested parties from abroad was first agreed to in 2013 by Jacob Zuma and the DRC’s president at the time, Joseph Kabila.

However, following allegations of early graft and corrupt back-door deals, the World Bank withdrew as a headline sponsor in 2016.

Environmental pressure group International Rivers also campaigned against the project, said to be an attempt at bloating infrastructure, and SA’s Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) found the project to be non-viable compared to more affordable alternatives derived from wind, solar and gas technologies.

Last year Radebe indicated that the IRP’s reasoning had been noted, but it has now emerged that SA’s role in the dam’s construction has apparently been secured.

This after Radebe notified Congolese authorities in December that the initial 2500mw SA will buy from the DRC to fulfil growing energy requirements, will actually be doubled to 5000mw.

This is despite South Africa’s energy demand dipping because of the sluggish economy.

Nevertheless, initial estimations were that buying 2500 from Grand Inga once its completed, including construction and maintenance of relaying power across several borders down south, will cost local consumers around R400m extra per annum.

With Radebe’s doubled pledge, that figure is set to increase substantially.

Speaking at the African Development Bank in July last year, the Spanish and Chinese companies involved in the construction of the dam said the project was simply not possible without South Africa’s buy-in.

The 11 000mw facility, including its transmission lines from the Inga Falls area to SA some 3000kms away, will cost around $18bn.

But a study by the University of California, Berkeley, has found that it will cost around $13bn annually while construction is under way and, considering the amount of time construction work is anticipated to take, Grand Inga 3 could finally cost about $80bn when its hydro-turbines are expected to start generating power in 2024.