Energy analyst Chris Yelland has reason to describe Eskom’s efforts over the last ten years to lengthen the lifespan of Koeberg as a “comedy of errors”.

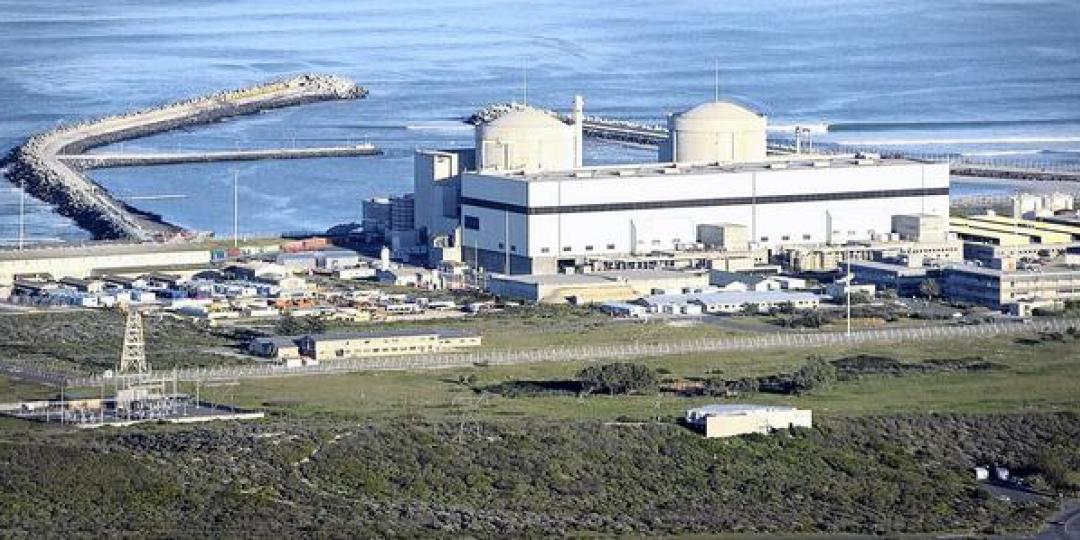

From as far back as 2012, the power utility had known for at least a decade that the nuclear power station’s continued use for South Africa’s grid was contingent on critical refurbishment, such as the replacement of six steam generators – three for each of the twin-reactor facility’s units.

However, delays and high-level dithering from the get go, not to mention the disastrous tenure of state capture enablers Brian Molefe and Matshela Koko, all scuppered the life extension work necessary to keep Koeberg going for another 20 years.

Currently Unit 2 at the power station has been off for longer than it’s been on this year, especially after work around the much-needed replacement of its three steam generators finally got under way in January.

The work was meant to have started several years ago but Eskom ran into difficulties, most notably a protracted legal battle with Westinghouse.

Lengthy attempts to get Eskom’s awarding of a contract for equipment to French supplier Areva overturned in the courts, meant work could not proceed.

Only once the American energy corporation exhausted all legal avenues to thwart Areva did it seem that the project, said to be the biggest in Koeberg’s history, could finally go ahead.

But then a series of industrial bungling followed, which begs the question, would things have been different had Westinghouse succeeded in its litigation?

First, Areva subsidiary Framatome found fault with the forging process of the generators in France.

To address the structural integrity issues of three of the generators, each weighing at least 250 tonnes, they were taken apart and flown all the way to an associate manufacturer in China for inspection.

“It took six Antonov aircraft to get the generators to the plant in China for inspection,” Yelland said.

“There it was found that the generators were definitely not up to scratch and it was decided to scrap them and start all over again.”

Yelland recalls how an official from Eskom at the time said: “This was the most expensive transport of scrap metal in the history of humankind”.

“Why they couldn’t just fly an inspection team to France nobody knows, but it would’ve cost a lot less.”

Then, after Chinese manufacturing of the generators was almost complete, one of the generators was dropped, meaning that the whole process was further delayed.

That generator is now only expected in December.

All this in the past, though.

Presently, Eskom’s resources have been stretched to the hilt with breaking equipment and diminishing expertise caused by events such as the departure in July of Riedewaan Bakardien, chief nuclear officer for Koeberg.

His emigration to Canada could not have come at a worse possible time for the power station, Yelland said.

Yet while Bakardien was still in his position, serious concerns were raised why the radio-active secure holding facility for the generators had not yet been completed, despite Eskom knowing for some time that these buildings needed to be in place before the generators could be replaced.

“It’s absolutely unacceptable,” Yelland said. “How can it be that they have known about this aspect of the life-extension work for how long and it’s still not done?”

He said it was initially estimated that it would take five months to complete the work around replacing the three generators of Unit 2.

“Then it became six months and here we are in September.”

When refuelling of Unit 2 and replacement work around the nuclear head of the unit was finished, Eskom managed to bring it back on line in August, only for the reactor to trip when the controlling rod malfunctioned.

“That’s a very serious problem” Yelland said, warning that this was a critical component to running a nuclear reactor that should not be taken lightly.

Not being able to run Koeberg at its full capacity, he emphasised, meant half of the station’s 1 840 megawatts (mw) were lost to the grid.

“That’s at least one stage of the current bout of load shedding we’re experiencing.”

But the country should perhaps be grateful that only 920mw of Koeberg’s capacity is currently not available.

That the entire power station may have to be shut down seems a distinct possibility.

Yelland explained that a licensing issue with the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) meant Eskom had only one operational licence for a station with two reactors.

Ideally each should have its own licence, which Eskom has apparently applied for.

A single licence for a twin-reactor station with significant infrastructural challenges means Nersa may have to withhold licence renewal for Koeberg if life-extension work to one of the reactors doesn’t meet with its approval, even if the other reactor works well or passes regulatory muster.

And that deadline, July 2024, is fast approaching.

“Eskom is running dangerously close to not making it in time,” Yelland said.

“Remember that Nersa must still do its own work, not to mention the risk of unknowns. Anything can go wrong with a project such as this and Eskom doesn’t seem to make provision for such eventualities. Basically, they don’t know that they don’t know.”